How “Crime Jazz” Became the Signature Sound for TV and Movie Detectives

In the 1950s and 60s, when Hollywood brought private eyes to the big and small screens, jazz was the music of choice to accompany their lives of danger and dames.

Film composer Elmer Bernstein once said that Hollywood turned to jazz “whenever someone stole a car.” To larceny, he might’ve added blackmail, kidnapping, infidelity and anything unsavory that transpired in a dark alley or seedy nightclub.

As a soundtrack to the hard-boiled television and B-movie crime drama that had its heyday from roughly 1950-1965, jazz evoked sex and violence. And for screen shamuses like Peter Gunn and Mike Hammer, a walking bass and a breathy tenor sax spilled style and swagger onto the neon-reflected city streets they walked, while catching the bluesy melancholy beneath their lone wolf personalities.

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]”Crime jazz”…was the sound of trumpets clenching into big brassy fists, socking their way through urban soundscapes.[/quote]

This brief evolutionary tangent of jazz, now called “crime jazz,” was the province of a handful of adventurous young composers, including Elmer Bernstein, Henry Mancini, Lalo Schifrin, and Kenyon Hopkins. Their cloak-and-dagger themes and incidental music mixed be-bop and big band with west coast cool and Latin jazz into a thrilling cinematic brew. It was the sound of trumpets clenching into big brassy fists, socking their way through urban soundscapes. Quite simply, if you were a TV or movie private dick during this era, you couldn’t crack a case in style without the accompaniment of crime jazz.

So how did detectives start to swing in the first place?

In the 1930s and 40s, the predominant influence on all Hollywood film soundtracks was classical music. Top composers of the era like Max Steiner, Victor Young and Dmitri Tiomkin accompanied – and sometimes overwhelmed – screen images with lush, romantic melodies and dramatic crescendoes.

Turn on Turner Classics at any hour of the day, and you’ll hear this type of soundtrack in all its purple velvet glory. Even when pop songs were included in a soundtrack back then, say “Night and Day” in Now Voyager, or the title song in Laura, they were gussied up in Brahms-style finery.

If and when a strain of jazz occasionally crept into a score, it was usually via a cameo of muted trumpet or tenor sax, to hint at some sexual undercurrent. There were a few exceptions, of course, most notably Alfred Newman’s groundbreaking soundtrack for Street Scene. In this 1931 picture, directed by King Vidor, all of the action takes place on a single New York City block from one evening until the following afternoon. To conjure up the metropolitan feel of the movie, Newman created a jazzy, rhythmic score that sounded like a second cousin to Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue.

But even in gangster and detective films of the time, such as Angels With Dirty Faces (1938) or The Maltese Falcon (1941), the action and dialogue were drenched in symphonic gloss. Looking back, there’s something slightly askew in seeing Bogey pulling a snub-nosed revolver out of his jacket while a violin section swells behind him. It almost makes you wish that some of the classic detective pictures could be retooled with new crime jazz soundtracks.

More Sax

A big change in Hollywood scores began in the late 1940s, via the film noir movement. With roots in German expressionist cinematography, the shadowy style of film noir (literally, “black film”) was a perfect visual foil for hardboiled crime dramas. And seminal titles like The Big Sleep, D.O.A. and Gun Crazy, with their tough, cynical characters, demanded a tough, cynical kind of musical accompaniment—something to subvert the standard Hollywood treatment.

At first, dark, bluesy strains crept into traditional orchestral scores by the likes of Miklos Rosza and Alex North. By the mid-50s, composers like Mancini and Schifrin were pushing the envelope even further, writing jazz-flavored scores for smaller ensembles. For the first time ever in Hollywood soundtracks, there were improvised solos. Gradually, the violins faded out of the picture, making way for trumpets and saxophones.

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]Crime jazz captured the mood not only of our post-war cities, but of a character as distinctly American as the cowboy – that soulful, solitary seeker of justice, the private eye.[/quote]

According to Lalo Schifrin (Dirty Harry, Bullitt), jazz was a natural fit for these hard-hitting screen stories. “Film making is not an individual art form,” he said. “It’s a collective, almost like a jazz jam session. It’s a gestalt. The director is the brain; the cameraman in the eyes; the film editor is the DNA; the producer is the lungs; and the composer is the ears.”

Oddly, many of the authors of the pulp detective stories didn’t feel the same affection for jazz. Raymond Chandler wasn’t much a music fan. Neither was Dashiell Hammett. James Cain preferred opera. And Mickey Spillane had his alter ego Mike Hammer digging the squaresville sounds of light classical.

Crime jazz reached its peak in 1959, a year of such standout soundtracks as Compulsion, Anatomy of a Murder, Shadows (director John Cassavetes used jazz to great effect in much of his work), and Odds Against Tomorrow (composed by Modern Jazz Quartet vibraphonist John Lewis). On television, the soundtracks of 77 Sunset Strip, Peter Gunn, Dragnet and Johnny Staccato were all high watermarks that showed that shamusing didn’t mean a thing without that swing.

No Respect

But by the mid-1960s, Hollywood soundtracks were changing again, thanks to the rise of rock ‘n’ roll, The Beatles, and the pop sound of Burt Bacharach. Crime jazz faded. (Not that it had ever been a chart-burning frontrunner.) At its height, it was rarely regarded as anything more than ornamental color for B-movies and TV dramas. To jazz fans, it had its moments, but as a genre, it didn’t place enough emphasis on extended soloing to lift it to the heights of Miles Davis, John Coltrane or any authentic jazz. And most of the name jazz musicians who played on these soundtracks did it for the money anyway.

Despite being one of the Rodney Dangerfields of popular music – ie, no respect—crime jazz has survived, resurfacing in unexpected places: the kitschy new wave of the B-52s, the noir-ish balladry of Tom Waits and the overall aesthetic of Steely Dan (the arrangements on the Aja album are pure gumshoe). And of course, crime jazz was an influence on all of John Barry’s classic James Bond spy soundtracks, from Goldfinger to Diamonds Are Forever, as well as the themes of 70s-era TV cop shows like Mannix, Columbo and Kojak.

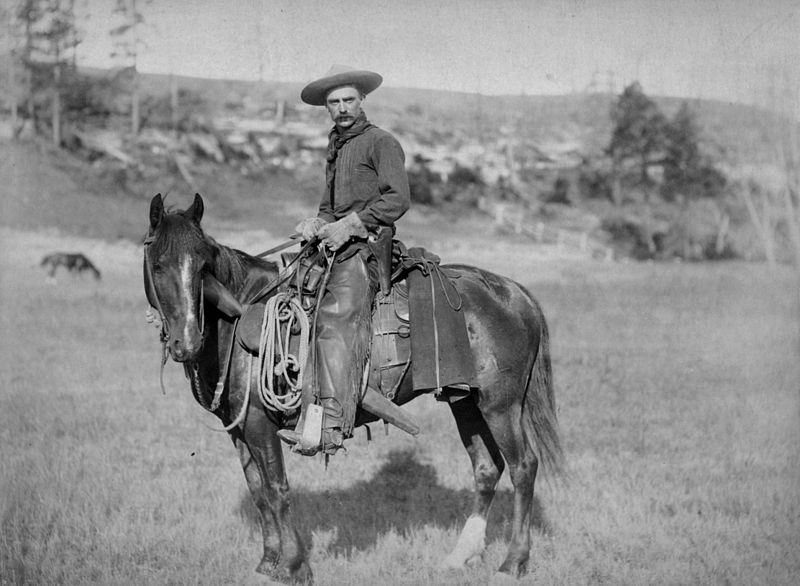

Today, it’s tempting to regard crime jazz with irony, as we often do with the pulp version of the private eye. But that would be to undersell its importance. The offspring of hard-boiled private detective fiction and jazz, two distinctly American art forms, crime jazz captured the mood not only of our post-war cities, but of a character as distinctly American as the cowboy – that soulful, solitary seeker of justice, the private eye.

Recommended Listening: 5 Essential Crime Jazz Soundtracks

The Wild One (1953) – The first mainstream Hollywood crime jazz soundtrack. Trumpet player and arranger Shorty Rogers cut his teeth in the big band era with Woody Herman and Stan Kenton, and would go on to help pioneer the west coast cool jazz sound. But here he (and fellow composer Leith Stevens) becomes Marlon Brando’s musical alter ego—all free-wheeling bop melodies and sexy swagger. Adding thrills and spills along the way are an ace band that includes drummer Shelly Manne, sax man Bud Shank and pianist Russ Freeman. Listen.

The Sweet Smell of Success (1957) – Though it’s not a detective picture, the characters of ruthless newspaper columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) and seedy publicist Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) have the hardened, cynical attitudes and nervous energy typical of private eyes. And Elmer Bernstein’s soundtrack is a marvel in the way it translates the sights, sounds and smells of 1950s New York City into frenetic jazz themes. Listen.

Anatomy of a Murder (1959) – Duke Ellington had contributed songs to a few B-movies and short subjects, but the invitation to score a major film with a top-notch cast (Jimmy Stewart, Lee Remick) and name director (Otto Preminger) gave him an expansive canvas. And Duke rose to the occasion, matching the twisted tale of revenge and murder with a virtuoso jazz score. Teeming with moody dissonance and action-packed flights of improvisation, the Anatomy soundtrack works as both a complement to the film and a free-standing album. Listen.

The Music From Peter Gunn (1959) – If you want to conjure up a private detective fantasy – concealed heaters, curvy dames, stylish capers – this is the perfect record. Composer Henry Mancini combined an ear for seductive melodies with an arrangement palette full of vibraphones, wavery guitars and swishing hi-hats to make some of the most memorable crime jazz ever. His soundtrack for Experiment In Terror is also a must-hear. Listen.

Johnny Cool (1963) – Billy May was one of Frank Sinatra’s favorite arrangers, especially when the Chairman was in a swinging, uptempo mood. With a varied background that included arranging for Glen Miller and many early NBC TV shows, May had a wide palette to draw from. This bloody tale of underworld vengeance gets plenty of socko brass, rat-a-tat drums and dense woodwind harmonies, plus a hip vocal theme from Sammy Davis, Jr. Listen.

Bonus (Sound) Track:

Music from Mission: Impossible (1967) – Composer-arranger Lalo Schifrin came of age in the bossa nova movement in his native Brazil. But his sense of dynamics was too visceral and hard-hitting to be contained by that cool Ipanema-style. During a fifty-year career, he has scored film and TV classics such as Bullitt, The Cincinnati Kid and Mannix, but Mission: Impossible remains his commercial peak. Titles like “Operation Charm,” “The Sniper” and “Jim On The Move” give you a hint of the crime jazz flavor within. And of course, the taut theme song remains one of the best-loved of the genre. Listen.