A young man befriends a dashing British diplomat, only to learn—years later—that his charismatic friend is one of the Cold War’s most notorious double agents.

It’s like a scene from a spy thriller: Adventurous young man meets erudite Englishman on a transatlantic cruise, shares many excellent cocktails, and strikes up a friendship. Years later, the American learns that his charming friend is one of the Cambridge Five, a group of British double agents who’ve been spying for the Soviet Union.

Except this story isn’t fiction. It’s just one episode in the daring life history of Stanley Weiss, a mining magnate and foreign policy expert whose accidental friendship with double-agent Guy Burgess proved one of the most influential of his life.

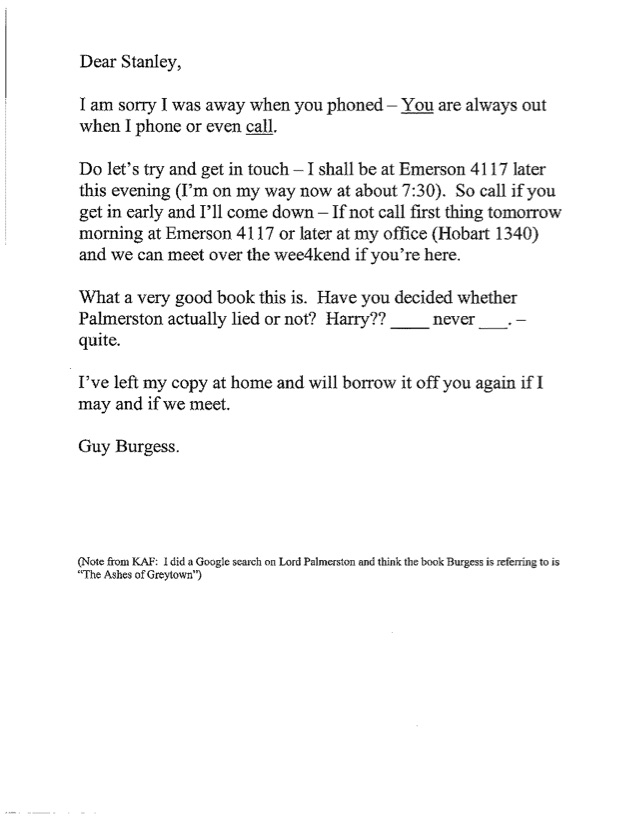

Below, you’ll find an account of that friendship, excerpted (with permission) from Weiss’s new memoir, Being Dead Is Bad for Business—along with several fascinating notes and letters Weiss received from Burgess before the Cambridge Five were discovered.

EXCERPT:

Having split up with my girlfriend in Paris, I sailed for home on July 28, 1950, on Cunard’s Caronia, broke and broken. I was traveling tourist class, but my London tailor’s art ensured no one would stop me when I walked into the elegant cabin-class lounge in search of a drink.

I noticed a man at the bar, drawing a strikingly vivid sketch of a 1941 Lincoln Continental convertible in all its glory. Fascinated, I sat down next to him and asked him about his meticulous doodle. He told me that his name was Guy and he was a British diplomat about to become the second secretary in the UK embassy in Washington.

I had no idea what such an officer did, but the title sounded impressive and important. We fell into a voyage of conversations, both of us drinking away every evening. He introduced me to gin and tonics.

Guy struck me as the epitome of an Englishman gentleman. In his late thirties, he was handsome and self-assured. He dressed with a mix of the rakish and the regal, just as I imagined a sophisticated Cambridge-educated diplomat would on an Atlantic crossing. I was charmed by his accent, which conjured up images of Cambridge evenings filled with wit and vintage port.

Guy struck me as the epitome of an Englishman gentleman. In his late thirties, he was handsome and self-assured. He dressed with a mix of the rakish and the regal, just as I imagined a sophisticated Cambridge-educated diplomat would on an Atlantic crossing. I was charmed by his accent, which conjured up images of Cambridge evenings filled with wit and vintage port.

I was amazed and impressed by the range and depth of his erudition. He was a virtuoso conversationalist, seemingly able to talk about anything: politics, books, music, travel. He served up a stream of stridently anti-American gossip. He pressed me to read Paul Bowles’s gloomy existential novel, The Sheltering Sky. He celebrated Beethoven in detail. He had holidayed in Tangier in French Morocco and loved its libertarianism.

I was in awe when he laced his tales with what “Winston” had told him about this and that. He invited me to his stateroom to see a book the great man had given him. He dug it out of his locker, where he kept his most prized books and documents. Sure enough, it said something like, “To Guy, in agreement with his views, Winston S. Churchill.”

After several rounds of gin and tonics one night, we went to the men’s room to pee. I was totally surprised when he reached over and tried to kiss me. I remember my first impression was that his face was scratchy. As usual, he hadn’t shaved.

After several rounds of gin and tonics one night, we went to the men’s room to pee. I was totally surprised when he reached over and tried to kiss me. I remember my first impression was that his face was scratchy. As usual, he hadn’t shaved.

I wasn’t homophobic, but the prospect seemed decisively unattractive to me. When I made it clear that there was no way we were going to have sex, he seemed not to mind.

He found lots of other guys on the ship to pick up, and every night, in addition to our usual rations of gin and his usual tour of the horizon, he would tell me about his conquests of the day, mostly to make fun of them.

Guy and I liked each other’s company, and by the time we arrived in New York, we had become friends. His shipboard friendship helped me in some important ways. For one, he gave me some direction. I needed to find a school by early September to get on the GI Bill, and I was running out of time. He told me I should become a diplomat and suggested I go to Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. He promised we could have fun together in Washington.

I enrolled in Georgetown in the fall of 1950. Guy kept in touch with witty notes on the embassy’s gold-embossed stationery, usually lampooning General Douglas MacArthur, whom he loathed. I still have the original copies of a few of the letters and notes he left for me, usually folded into fourths or eighths and wedged into my mailbox or slipped under the door. One of them, dated December 31, is a handwritten note that Guy titled “Weeks Celebrated in U.S.A” with the caveat “Incomplete List,” added in parentheses just below the title. It lists twenty-seven fictitious “weeks” observed in the U.S.—from “National Honey for Breakfast Week” to “Posture Week” to “Leave Us Alone Week”—each of which joked about things we laughed about then during our many discussions together, almost always over a glass or two.

I loved going to dinner with him every two or three weeks, just the two of us. I enjoyed the buzz he created with my friends at school—this dashing British envoy who picked me up in his swank 1941 Lincoln Continental convertible with its prestigious diplomatic plates.

Guy always had in his possession a bottle of bourbon, and I liked drinking with him. The last night I saw him, we went to the movies to see Irene Dunne play Queen Victoria in “The Mudlark.” We were sitting in the back row, passing the bourbon back and forth, when Guy dropped the bottle. It rattled and banged all the way down the slope of the floor and finally broke, provoking everyone to clear out of the theatre.

As we headed out, Guy suggested we go to his place, a basement apartment in the beautiful home of one of his colleagues.

Guy’s host, Kim Philby, a strikingly handsome man, came in and sat down to chat. He also liked bourbon. Guy had already told me his friend was a spy, a key officer in the embassy’s intelligence operations. I was too impressed and too naïve to appreciate this indiscretion. The two of them proceeded to swap speculations about which notables in their crowd and around town were homosexual. I was so star-struck, I didn’t consider the oddity of their conversation.

A few weeks later, I went to see a movie that changed my life. “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” was about two Americans who moved to Mexico to hunt for gold. The movie roused in me an appetite for adventure.

When the spring semester was over, I drove home to Philadelphia, and told my mother that I had made a decision to move to Mexico. I left a week later. But before I did, on Thursday, June 7, 1951, I unfolded the Philadelphia Bulletin to see how the Phillies were doing, and I was startled to see a screaming front-page story about my friend Guy Burgess. It said he and Donald Maclean, a senior diplomat who had been posted with Burgess at the British embassy in Washington, were suspected of being Soviet spies. The British government believed they were on the run and had launched a massive manhunt to find them.

When the spring semester was over, I drove home to Philadelphia, and told my mother that I had made a decision to move to Mexico. I left a week later. But before I did, on Thursday, June 7, 1951, I unfolded the Philadelphia Bulletin to see how the Phillies were doing, and I was startled to see a screaming front-page story about my friend Guy Burgess. It said he and Donald Maclean, a senior diplomat who had been posted with Burgess at the British embassy in Washington, were suspected of being Soviet spies. The British government believed they were on the run and had launched a massive manhunt to find them.

I learned later that Guy had abandoned his vintage Lincoln Continental at a local Washington garage and had left his prized book autographed by Churchill at a friend’s place in New York. Kim Philby turned out to be a third man in the operation, which history would remember as the highest-profile and most costly conspiracy of the Cold War. When the British finally flushed him out a decade later, he fled, like Burgess and Maclean, to Russia, where the three lived the rest of their lives in exile.

I later read that Guy had an especially bad time of it in Moscow. Early on, a street gang beat him up and knocked out his teeth. The Soviets frowned on homosexuals and took away his privileges. He slid further into alcoholism and died a lonely death in 1963, pining for his homeland.