The story of the world’s first private investigator — a former criminal who used his street savvy and underworld network to pioneer the science of criminology

The modern art of private investigation is an impressive mix of human savvy and up-to-the-minute technology.

The modern art of private investigation is an impressive mix of human savvy and up-to-the-minute technology.

Fraudulent insurance claimants, misbehaving domestic partners, and missing witnesses can be tracked down and photographed, videoed, or recorded quicker than ever before, and the results of such cohesion between man and machine have helped solve countless disputes and saved a fortune in unnecessary pay-outs.

Yet it all started somewhere, with one man deciding to set up an agency to investigate crimes and secure information through clever surveillance and spying.

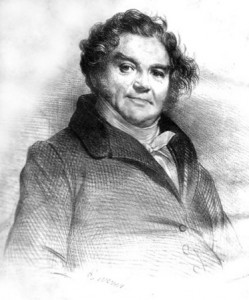

That man was Eugène François Vidocq, born in Arras, France in 1775 and, for much of his life, a criminal himself. He founded the state crime detection agency Sȗreté Nationale in 1812, remaining its director until 1827. As such, he is considered the father of modern criminology, whose story inspired such great writers as Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens.

Early Days

How did Vidocq turn so dramatically from his criminal past to become the first ever private detective?

Born into a large, wealthy family, he turned to crime in his youth, stealing and selling his parents’ silver plates when he was just 13 years old, and spending the proceeds in a single day. His father had him jailed to teach him a lesson. In 1791, Vidocq joined the army, building a reputation as an expert swordsman.

Despite his talents, the young Vidocq seemed guided by his shadier instincts. He was a womanizer, often in trouble for dueling, and later, for desertion. After leaving the army, he committed various thefts and frauds, spending time in and out of jail. He was sentenced to hard labour for forgery in 1796 but managed to escape in 1800.

The Path to Redemption

Vidocq’s redemption began some years later when he witnessed the execution of a man who had started him off on his life of crime. This affected Vidocq deeply, and he moved away from his local area, trying to live honestly as a merchant.

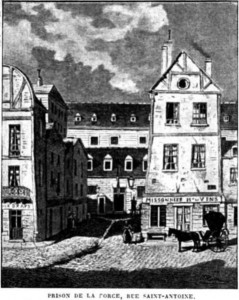

However, when various characters from his past emerged, blackmailing him for money, Vidocq offered his services to the police as an informant. In 1809 he was placed as a spy in a Parisian jail, where he reported on his fellow inmates.

On his “release” from jail 21 months later, he continued to work for the police force, immersing himself in the criminal underworld to gain information.

Excerpt from Memoirs of Vidocq: Master of Crime:

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]”I believe I should have been a permanent spy, so far were the prisoners from supposing that there was the slightest connivance between the agents of authority and myself. Even the jailers and warders did not suspect the mission entrusted to me.” —Eugène François Vidocq[/quote]

Master of Disguise

By 1811, Vidocq had become an expert in criminology, a strict record-keeper, and a ballistics expert. He was a master of disguise—often dressing as a beggar, the better to disappear into the Parisian underworld. He organized an informal “plain clothes” police force, which was converted to a security police unit once its value was realized by those in charge.

It was given the official name of Sȗreté Nationale by Napoleon Bonaparte, and its staff of 28 ex-criminals and former convicts covered the entire city of Paris. Vidocq’s unit got good results. By 1820, they had significantly reduced crime in Paris, and Vidocq was living on 5,000 francs per year. He supplemented this already princely income by working on private investigation cases alongside his main duties.

Excerpt from Memoirs of Vidocq: Master of Crime:

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]”One can see what my task was: I had to go to all the disreputable places in the city…Woe betide the agent who was found there, no matter what the reason. He would inevitably been beaten to death. The gendarmes did not even dare to show themselves, so imposing was this assembly of bad lots. I was less timid, and I did not hesitate to risk myself in this herd of wretches…

“It was while I was drinking with these gentlemen that I learned about the crimes they had committed or premeditated…I can say that I inspired in them a boundless confidence…” —Eugène François Vidocq[/quote]

Friends and Enemies

Despite his success, Vidocq remained a wanted criminal. His superiors repeatedly requested a pardon for him, but this did not happen until King Louis XVIII in 1817 signed the requested paperwork. After he resigned from the agency in 1827 he founded a paper factory, employing several ex-convicts — a move that led to scandal and his eventual bankruptcy.

Returning to his criminology roots in 1833, Vidocq founded Le Bureau des Renseignements (Office of Information) — a private investigation agency, once again staffed with ex-convicts. This proved highly successful to begin with, but Vidocq’s extralegal methods got him into trouble with local authorities, who charged him with several crimes (later dismissed). He’d also made several powerful enemies, who brought lawsuits against the business.

Although Vidocq successfully appealed, his reputation was irrevocably damaged, and his business suffered. He withdrew further and further into private life, ending his days quietly. He died at age 82 in 1857 at his home in Paris. His wife had died a decade earlier, and the couple left no children.

World’s Greatest PI

Vidocq’s extraordinary life paved the way for the modern private investigation business. His memoir, published after he resigned from Sȗreté Nationale, became a best-seller all over Europe and established him as the world’s first private investigator.

His fascinating story of criminality followed by redemption inspired many iconic literary characters, from Les Misérables’ redeemed thief, Jean Valjean, to Magwitch, the convict and philanthropist from Great Expectations. And his notoriety helped shape modern PI mythology in life and fiction — the shadowy shamus who marries noble intent with questionable methods.

Many of the investigative methods pioneered by Vidocq are still in place today. He would have firmly embraced modern surveillance techniques and technology, as ways of getting the job done as quickly and effectively as possible. Vidocq’s desire to help the innocent of Paris while he hunted down the guilty sharpened his skills and acted as his inspiration for the work he carried out – something that should be at the heart of every private investigation agency founded since.

Related article: How Dashiell Hammett Invented the Modern Detective Novel

About the Author:

Brian Davies is the Director of BDL Investigations, a private investigation company based in the southeast of England. After setting up shop in 2005, Brian has built BDL Investigations’ network of investigators, who now cover the whole of the UK, including a dedicated surveillance / observation team.