In Pursuit, we’re offering highlights and transcripts from our monthly webinar series, starring fellow investigators with expertise to share.

Since early 2017, PursuitMag and PIeducation have offered a webinar on the last Thursday of every month (minus holidays) featuring Pursuit editor Hal Humphreys interviewing expert investigators on topics from surveillance to business best practices.

Over the next year, we’ll post recaps of our favorite webinars, including an edited transcript, screen capture images, links to resources mentioned, and time codes from the video, in case you want to listen to a section on one specific topic. We hope you’ll find this a useful resource, and please do subscribe to our YouTube channel.

In the meantime, here’s Hal speaking with Brian Willingham on open-source intelligence, a webinar from Sept. 28, 2017.

Introductory Intel

HAL: Brian Willingham is one of the best investigators in the country when it comes to open-source research. He also has one of the most amazing blogs in the PI community—good tips and tricks to make your life easier as a private investigator. Ladies and Gentlemen, Brian Willingham. Brian, tell us who you are and what you do. (3:30)

BRIAN: I’ve been a private investigator for about 15 years. I started at my father’s investigative firm in Westchester County, NY. I joined the industry at an interesting time. [My father] did a lot of insurance claim work, a lot of surveillance. Companies were bearing down on these firms to lower their fees. The firm started going more after law firms, things like that.

Because of the growth of the internet, online research became a big selling point: open-source intelligence, court records, media records. So I grew up in the business in that age. Over time, it’s become my niche. I work for law firms, big investigative firms, in NYC and around the world. I’ve been on my own for eight years, and I started this blog seven years ago. I write about stuff that’s interesting to me. It was meant as a tool to market to potential clients, but I’ve got this huge following of other investigators, which has been great.

Why Blog?

HAL: You sometimes get called out by other investigators for sharing tips they feel you shouldn’t. Talk to me about blogging and why you do it the way you do.

BRIAN: One of the things I dedicated myself to early was becoming open and transparent about how I operate. And I think for most investigators, that’s an uncomfortable position to be in, in part because there’s a little bit of cloak and dagger stuff going on in our business; people don’t want to reveal their secrets—secret sources, or secret ways to obtain information, which are really not secrets at all.

Part of my ethos is that I’m this transparent guy. If you get to know me, I speak my mind. I curse like a truck driver. What you see is what you get. That’s just who I am. And I want to develop my business around that. I started blogging, just talking about stuff I do, and I’ve been called out a lot on it. There are close friends of mine who say, “What are you doing? You’re giving up our secrets.”

I get a lot of inquiries online from people who say, “I really like who you are and what you’re about.” It attracts people who are like minded. I’m not going to get a guy who wants to steal his wife’s car or break into somebody’s house. Those people aren’t going to call me, because they can read on my website that that’s not who I am.

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]I’m not going to get a guy who wants to steal his wife’s car or break into somebody’s house. Those people aren’t going to call me, because they can read on my website that that’s not who I am.[/quote]

What is open-source intelligence?

HAL: I can say that Brian does indeed speak his mind. That’s one of the reasons we get along so well. Let’s jump into the topic. What exactly IS open-source intelligence? What does it mean? (10:30)

BRIAN: I put it in a broad category: anything I can find open and freely without any restrictions. It doesn’t require me to have a special license. Anybody can get this stuff. It’s just a matter of knowing where to get it.

So we’re talking about anything that’s available on the internet, anything at the public library. And public records would be any government-issued document—court records, or corporate records, litigation judgments, liens, registration documents for certain professions.

Social media has become a big part of open-source intelligence. So it’s basically anything I could sit behind my computer and get, or resources that might NOT be digitized: historical newspaper clippings, historical property records, anything that might be valuable.

How to Begin an Investigation

HAL: There are so many places to find information. The hours upon hours spent in the bowels of some courthouse, or some newspaper office, digging through clippings. That’s intelligence, and it’s available.

When you get an assignment, where do you start? (13:38)

BRIAN: First, I always go to Google. The research I do is really really in depth. I’m spending ten, twenty, up to a hundred hours researching a topic, a person, or a company.

I’m going to use you as a guinea pig today: When I Google Hal Humphreys, what’s his deal? Is he prominent? What businesses has he been involved with? Does he have social media profiles? Has he written any books? Just to get a general sense about him. But I’m also trying to see if there are eighteen other Hal Humphreys: Am I going to be digging into dozens of searches hundreds of lawsuits to identify the right guy? I’ll spent a good half hour to get a sense of what I’m getting myself into, and picking up little clues about who they are.

One of the things about Hal that some people don’t know is that his real name is not Hal. That’s critical when you’re doing research: You want to know what their real name is and what their nickname is, because most official documents—corporate records, property records, criminal records—will have their official name, but other records may not—their social media profiles, or civil litigation. So that’s where I always start.

HAL: A simple Google search for Hal Humphreys, you can see different versions of the Hal image, but about four lines down, you see a picture of Brian Willingham. (laughs)

BRIAN: I’ll show you a quick example: If I’m doing research on me, you’ll see there’s a gentleman who was with the Flint police department who wrote a book about the soul of a black cop, so obviously (that’s not me). Those are the things I’m trying to figure out: Are there other prominent people named Brian Wilingham? This guy is in California, another guy in Michigan. I can ignore those.

Deep Web Searches

HAL: Let’s talk about the Deep Web and the Dark Web. What is a Deep Web search? What does that mean? (19:00)

BRIAN: Obviously there’s this whole sketchy area with Tor, and people selling human body parts on the Web, and buying credit card numbers and social security numbers, things like that. But I think for our purposes, it’s stuff that’s not available on the surface of the internet, not on a Google search. So you’d have to go to a separate source to search something.

Some estimates suggest that Google’s indexing only covers about 3% of what’s available on the internet. There’s millions of data points that aren’t on the “surface Web” because Google is not smart enough yet to type in a name and have all those results indexed by Google. So there’s millions of cases of that: library databases, news media databases, court records, property records, tons of information that wouldn’t be on the surface.

Facebook is another example. Not everything is indexed on Google for Facebook. Sometimes you have to have your own account on Facebook, and even beyond that, people turn on privacy features that don’t allow you to obtain anything on their profile. So there are layers upon layers of information that is technically on the internet but is sort of Deep Web/Dark Web, beyond a normal surface search.

Top-Secret Investigative Superpowers

HAL: People think private investigators have secret powers. Sometimes, we know tricks that can help people get information faster. What is your favorite top-secret superpower? (21:48)

BRIAN: There are a couple of sources that have broken open cases for me. One is archive.org, a website that captures historical information on various websites. The Web is a living, breathing thing. Archive.org captures historical points—not every day, and only certain websites. But it can be enormously valuable.

BRIAN: I’m doing a case right now where I’m trying to identify connections between two parties. Part of my research is going to be digging through archive websites and trying to find out if these guys worked together. So archive.org has broken open so many websites for me, I can’t even count.

The other one is DomainTools. Most people know you can do a WhoIs search to determine who the owner of a domain is. Domains have to be registered under a name. But more and more, people are registering under a proxy so they can hide who’s registering the website. DomainTools, similar to archive.org, captures who owned a website over a period of time. So people are becoming conscious of protecting their privacy, but they may not have been so safe in the past.

You look up the WhoIs, and it’s a proxy, but if you go into the historical domain information, you might find little nuggets about who originally registered the domain, if it was transferred from one person to the next. This has been helpful to me in dozens of cases.

The other thing it offers is search features. I can search all the registers of all the domains for all time, under a certain name, by address, email, a phone number. These aren’t giant secrets, but they are a couple of website that have done wonders for me.

HAL: The historical information you see on domain registry, is that available at WhoIs? (26:45)

BRIAN: No, WhoIs will provide you with the updated, current owner of a website. Any historical information, you’d have to go to a third party to get. Most of their services are paid services.

Proprietary Databases

HAL: I get this question a lot: What proprietary databases do you use, and what do you use them for? I ask because a lot of PI firms will take a TLO search, for instance, change the header and footer to their own logo, and turn that in as a “background investigation.” (28:18)

BRIAN: I consider databases to be a starting point in any type of investigation. I am a huge proponent of multi-sourcing every search I do because I don’t trust any database.

Being able to pinpoint a specific address—TLO, IRB, TracersInfo, Skip Smasher, whatever you want to use—they all provide pretty good, up-to-date information about address history. It’s not always accurate, though. So I will always go to something like an assessor’s office, the GIS or property records, and figure out whether they actually own the address.

I use a variety of databases. TLO is one of my primary sources, because I find it to be very useful and easy to use. Their information is generally pretty accurate. I don’t rely on it 100%. I’m interested in phone numbers, and they tend to provide a lot more phone numbers than some of the others. LexisNexis, I rely on pretty frequently. I have a full subscription to their public records research, which is several hundred dollars a month. It’s an enormously valuable tool to me. If I had to choose one, that would probably be one of the ones because it’s got so much incredible information.

Other Search Resources

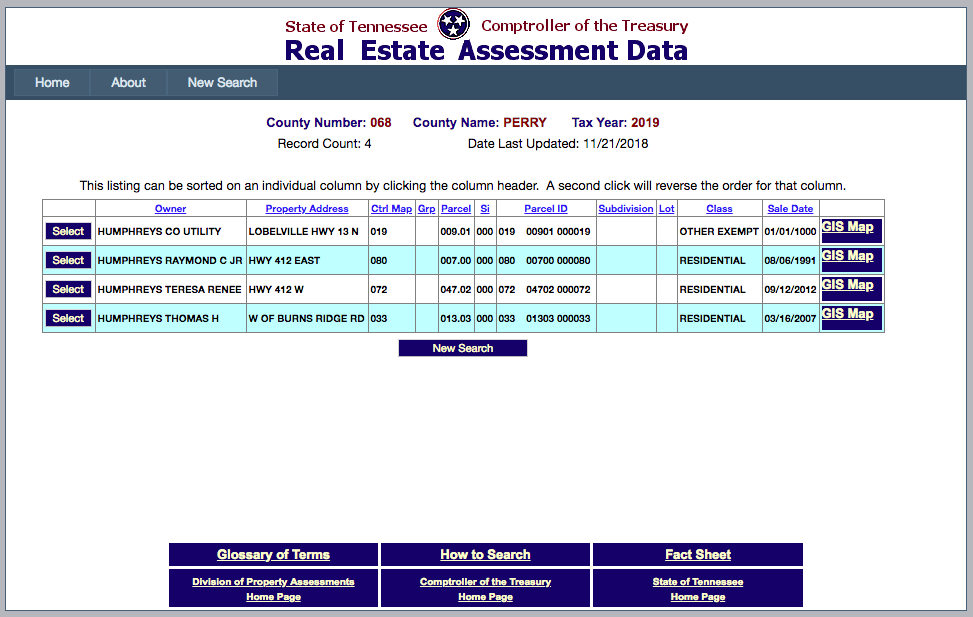

HAL: Let’s go back to secret resources that people don’t think about. For instance, if you’re trying to locate a witness and you’re trying to find a piece of property they own, you have some info on them but you’re not sure—most property assessors will have an online portal where they provide their records online. Here’s Tennessee’s real estate assessment data site.

I’m going to do a quick search here: Perry County, TN, we’re going to look for property owned by Humphreys. As Brian mentioned, my actual name is not Hal, that’s a nickname. My name is Thomas Humphreys. So I did a quick search on that.

We’re looking down the screen—at the bottom, Thomas H Humphreys. Pretty sure that’s me. Click on that, and there’s all kinds of public information available to anybody. Here’s another fun thing: If you click the GIS link you can actually see where the parcel is.

I’ve used this to identify witnesses and where they live. That’s one example of Deep Web research. If you know where to find it, it’s available. Brian, what are some resources that people might not have thought of before? (34:15)

BRIAN: One of my secret sources is Facebook. You can type anybody’s phone number up in the search box and it’ll pop up anybody that might be associated with that [number]. It’s an interesting tool if you’re trying to verify that somebody is associated with a phone number.

The other thing I love is there’s all this fascinating information on Facebook that’s not publicly out there. One of the websites I use is inteltechniques.com. It’s an absolutely fabulous source.

If you go into this Intel Techniques tool, you paste the Facebook user name into this little screen, and if you hit Go, you get his Facebook user unique information. Let’s use Zuckerberg. What you see is, using the unique ID number, you can do a lot of interesting searches. Tagged photos—not necessarily photos [someone] posted.

[Go to YouTube video: 37:45-40:50 for screen shots of a sample FB search for tagged photos.]

BRIAN: That can be enormously valuable thing in your investigation. I worked an investigation all last weekend and spent about eight hours mining Facebook. I was trying to identify connections, and it was an enormously valuable tool for me.

The other one I’ll mention is a tool from intel-sw.com. It allows me to search Facebook for a particular person by name. (example at 41:23) Where it gets interesting is you can add in all these characteristics. So if I wanted to find a “James Marshall” who lives in California, I can do that. I can narrow down even further by where they work, if they ever worked at Google. There, I found my guy.

The point is, I’m trying to find people who fit certain characteristics. I use that tool all the time. They have some of these tools at Intel Techniques as well.

HAL: I think this is a good place to point out: If you’re doing open-source research, you can spend hours following different trails. You’ve got to narrow down the way you approach things.

Let’s go to questions: Brian, what’s your favorite way to find a phone number? (45:45)

BRIAN: Proprietary databases. Time is of the essence. People pay a lot of money per hour, and I don’t use the free stuff. I go to TLO to get a number quickly.

HAL: One reason we pay so much for these databases is they have the most current information you can have. If you can afford it, it’s good to have two or three to cross reference. You still have to be sure that information is accurate. But we’ve all got to pay the bills, so we can’t take too much time to find a phone number.

Organizing and Archiving Your Investigation

HAL: Another question: How do you save and organize the data you find on all these sites during an investigation? (48:45)

BRIAN: One is Hunch.ly. It sits in the background and records everything you’re doing. When you’re investigating, you go down hundreds of rabbit holes—you might go to a website and forget how you got there, or click out of it and never see it again. With Hunch.ly, it saves all that in the background. It’s constantly monitoring what you’re searching and saving everything, and even if it disappears from the Web, it’s there.

The other thing is, I save a lot of things as PDFs. When I’m doing TLO or LexisNexis research, I’ll print screens as PDFs. I wind up having hundreds of documents in my folder, and I’m also keeping a checklist along the way. It’s a critical part of this. If you do criminal defense work, something that’s going to court, I would strongly consider using Hunch.ly.

I had one case where an article disappeared off the Web that was critical of a gentleman that was in the oil business. He was going to be the owner of a major sports team, and I was able to retrace my steps through archive.org. But something like Hunch.ly would have been helpful. So definitely check that out.

HAL: I use Hunchly as well, thanks to Brian’s introduction. It’s a fantastic tool.

A couple of questions coming in about criminal databases: I do a lot of work in Texas, and the databases we use often don’t have current information because the Texas Dept. of Public Safety collects information at the county level, but not all the counties report it in a timely fashion. So especially for criminal histories, you might need to call the county and find out if there’s new documentation on that person.

Another question in: What happens when you save images or pages but the subject erases them? Is your image capture acceptable in court, or can you save the metadata to prove it existed and is not doctored?

BRIAN: I don’t do a lot of cases that end up in court. But I save PDFs that include metadata. I don’t know if that’s the best way. There was one case where we knew a lot of stuff was ultimately going to disappear from the Web, and we wanted to capture it and have it admissible. At page-vault.com, the way they capture the information makes it admissible in court. They will provide an affidavit showing it was captured on this day, and that it has not been doctored. So if you know a page is going to be taken down, there are a number of services like Page Vault that will capture it.

HAL: The thing I like about Hunch.ly is that it saves every step along the way, so you would need to talk to your attorney about what is admissible, but I have found Hunch.ly to be the most robust tool to show exactly what I did, all the steps I took. And if you approach your research in an organized fashion, that’s going to show up on Hunch.ly as well. (57:30)

BRIAN: Also, about criminal records: I think it’s one of the most widely misunderstood topics, even amongst investigators. There is NO ONE DATABASE that will capture all criminal records. The reality is most of them are full of bullshit. Many states don’t sell information to database providers, including New York. A lot of my subjects are here.

A couple of tips: Whatever database you use is better than nothing, but never rely on one database. Use some sort official data. Below is a map I put together on my site of states that offer statewide criminal checks. Click on New York, it gives you details—it’s $66. It’s the only way to do it, and other states have these services.

BRIAN: A word of caution: The Texas Dept. of Safety has a $3 search you can do. It is completely reliant on the local agencies supplying this information to the department. Studies suggest that 30-40% of the information actually gets there, so even a state agency isn’t completely reliable. You need to do as many onsite searches as you can, physically go to the court, use the court website. Use multiple sources to identify criminal records, and make sure you’re hitting all the places the person has lived.

HAL: Open-source research is such a big topic, it’s impossible to cover in one hour. If you have not taken Brian’s open-source research master class, you need to do that. It’s ten hours of Brian talking about his tips and tricks, showing you the tools, and some takeaways to improve your investigative skills.

BRIAN: One last thing: There are no magic secrets to what we do. It takes time, effort, and research. It’s about knowing the tools exist and how and when to use them. In a lot of cases, it’s just about putting in the time and effort.

Resources and Sites Mentioned in This Webinar:

State real estate assessor sites, such as this Tennessee site

Diligentia Group’s US Map of Criminal Checks by State

Brian Willingham’s PIeducation Master Class