How the Best Con Artists Manage to Fool Most of the People Enough of the Time…No Matter How Smart We Think We Are

In any swindle, there are at least two minds at play: the swindler’s, and the mark’s. Gifted con artists don’t lift our wallets; they convince us to hand over the money willingly. They persuade us to play a game that’s rigged for us to lose, by exploiting our vulnerabilities.

Internet romance scammers exploit people’s fear of loneliness. Ponzi schemers exploit people’s greed, or their fear of financial risk.

And grifters of all kinds exploit the innate human desire to believe.

That’s why, even in the wake of a $65 billion Ponzi scheme that sent seismic tremors through the world of finance, there will always be more Madoffs.

That’s why, even in the wake of a $65 billion Ponzi scheme that sent seismic tremors through the world of finance, there will always be more Madoffs.

“A world immune to Ponzi schemes is a world utterly devoid of trust, and no one wants to live in a world like that,” writes Diana B. Henriques in The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust. “Indeed, no healthy economic system can function in a world like that. So right now, some new Bernie Madoff is exploiting our need for trust to build another world of lies.”

Right now, somewhere in the world, this budding Madoff is insinuating himself into a community, gaining people’s confidence, and setting his trap for them.

From the epilogue:

“Whatever their niggling doubts, they are reassuring themselves right this minute about how trustworthy he is, as he spins out his vibrant, beautiful web of fantasy.

“Later, when that new world of lies is torn apart, they will…brand him an evil, inhuman monster. But if they are honest with themselves, they will have to admit that he was recognizably, shamefully human every step of the way—just like the last Bernie Madoff and the first Bernie Madoff…

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]”That is the most enduring lesson of the Madoff scandal: in a world full of lies, the most dangerous ones are those we tell ourselves.”[/quote]

Does all this mean we’ve learned nothing from Madoff and his predecessors? If there are lessons, perhaps they are that we don’t truly know our own minds: We aren’t as rational as we think we are. And no matter how skeptical and savvy we believe ourselves to be, we cannot reliably spot deception.

The most we can do, perhaps, is to educate ourselves about the minds of confidence men —and about our own psyches. Because as Henriques points out in The Wizard of Lies, Madoff illustrated a difficult truth about the unseen Ponzi schemer among us: “He is not ‘other’ than us…He is just like us—only more so.”

In Part 3 of our series of interviews with NYTimes financial writer and author Diana B. Henriques, we explore the psychological tricks fraudsters play on us — and on themselves — along that path to ruin we tread together.

1. They play the role people expect to see.

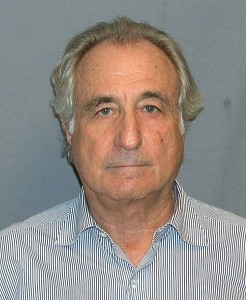

To understand how (Madoff) could’ve fooled the regulators for so long, you have to make an imaginative leap: He was a Wall Street statesman. They trusted him. He’d built a firm from scratch that had become one of the top 50 firms on the street.

He was a trailblazing, hugely successful entrepreneur. At one point, his firm was trading 5% of the daily volume of New York Stock Exchange listed stocks, in afterhours trading, what they called the “third market.”

The day he was arrested, I went back into the Times archives to see the last headlines about Bernie Madoff. You know what the first one I found was? It was a little story about a new electronic trading system being developed for Wall Street, kind of a computer-driven way of trading stock, and his partners in that deal were Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and Citigroup.

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]He was a Wall Street statesman. They trusted him…No one expected to see Bernie Madoff as a criminal.[/quote]

It is very hard, in hindsight, to go back and see the Bernie Madoff that existed in the minds of regulators and the public before his arrest. It’s hard to wipe out what we know now and see him based on what they knew then. He was respected, admired, and trusted.

A psychologist will tell you that we tend to see what we expect to see. We miss what we don’t expect to see. No one expected to see Bernie Madoff as a criminal. It’s like the dancing bear in that wonderful video or the gorilla on the basketball court.

2. They belie the stereotype…except when they don’t.

What makes it especially hard is that sometimes the (conman) stereotype is correct — for example, Sir Allen Stanford, the “Ponzi Peer,” was the classic stereotype of a Ponzi schemer. His high-flying jet, two girlfriends on each arm, the big-living, larger-than life-personality; tall, imposing, well-spoken; he was, to my mind, the classic Ponzi schemer.

The notion that that’s what all Ponzi schemers are like is totally mistaken. Bernie wasn’t. And I bet if we looked at the long, long history of Ponzi schemers, more of them were like Bernie than were like Sir Allen Stanford. Bernie’s investors would’ve been immediately suspicious of a character like Sir Allen Stanford — pushy, charismatic.

3. They offer a good deal, not a too-good-to-be-true deal.

There’s also an embedded belief that Ponzi schemers inevitably offer pie-in-the-sky returns, too good to be true returns. That’s not true. The ones that blow up fast, yes — that’s true, because they run out of money too fast. But Bernie was offering, for most of the years of his life and to most of his investors, subpar returns.

You could’ve made more money in the Fidelity Magellan Fund than Madoff investors made through most of the modern life of his fraud. He wasn’t offering sky-high returns. He was offering safety — steady, consistent returns. Nothing in that would’ve instantly waved a red flag at anybody’s face.

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]The smart Ponzi schemer will be offering you something that is just good enough to be attractive but never too good to be true.[/quote]

Regulators and the rest of us often assume that someone offering to double your money in 20 days, clearly that’s a Ponzi scheme. Somebody offers you a nice, safe short-term bond fund that today is paying you 2.5% a year with total safety: That doesn’t sound like a Ponzi scheme, does it?

There is no totally safe short-term investment you can buy in the market today that remotely approaches 2.5%. They all are paying much less than that. And yet you didn’t immediately say, “Oh my goodness, no one can be offering that, could they?”

The smart Ponzi schemer will be offering you something that is just good enough to be attractive but never too good to be true. One line I use at my speeches which I stole from a marvellous fraud analyst named Pat Huddleston is that if it sounds too good to be true, you’re dealing with an amateur.

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]If it sounds too good to be true, you’re dealing with an amateur.[/quote]

We want to believe that if we just steer clear of these wild pie-in-the-sky offerings, we will be able to protect ourselves from Ponzi schemers. The people of the Stanford Ponzi scheme, what were they buying? They were buying bank CDs from a foreign domicile bank. And because it was foreign domicile, they spun a story that explained how their returns were slightly better than the returns offered by the US banks’ CDs.

But these were not people looking for 50% in a month. These were bank CD investors. They were looking for safety and a little bit better yield, and they fell for it in their thousands.

That was the second largest Ponzi scheme in history, at roughly $11 billion of “safe” bank CDs. So one of the biggest questions of the Madoff scheme is if you think pie-in-the-sky returns are the key red flag for a Ponzi scheme, you’re absolutely wrong. Dead wrong.

It’s going to be the slightly better, a little bit more attractive, a little steadier, and consistent investment that’s going to lure you in.

4. They exploit people’s desire to believe.

I don’t think you can travel through the personal destruction that a Ponzi scheme leaves behind without gaining a profound appreciation for how much we want to believe in one another, and how, even when the evidence starts to mount, we will resist admitting we were wrong. We will resist admitting we were betrayed.

The power of self-delusion — wanting to believe the best of ourselves and the best of other people — remains the con artist’s most powerful weapon.

5. They leave a huge mess in their wake, destroy lives, and sleep soundly.

I actually had a somewhat similar blinding revelation about my dad when I was a child, something that stuck with me for life. And the very night we learned that Madoff’s sons had turned him in, the feelings I’d had when I learned about my father — something I never dreamed to be true — that just blew up in my mind. What they must have experienced! I really did bring to this, as my very first response to this story, a faint echo of what that feels like.

My father’s transgressions were nothing like Madoff’s. I was relatively young, and I moved on. But (his family) lived their entire lives believing this. Ruth (Madoff) fell in love with him when she was 13 years old!

My father’s transgressions were nothing like Madoff’s. I was relatively young, and I moved on. But (his family) lived their entire lives believing this. Ruth (Madoff) fell in love with him when she was 13 years old!

Suddenly, everything they thought was true about their life was proven to be a lie. They were standing in thin air. There was nothing, no foundation they could believe in at all.

If you count all the victims here, surely, among those most tragically damaged were the Madoff family, who not only lost all of their money but lost all of their standing in society (which most of its victims did not), lost all of their friends and close relative connections (which most of the victims did not), and lost their entire past.

The unthinkability of that, I think, is why so many people assumed that Ruth, Mark, and Andrew must have known. Because it was so unthinkable that you would suddenly wake up and find that your husband or your father was a lifelong fraud, that everything he told you was wrong.

Unless you’ve experienced that, you find it hard to believe it could actually happen. But if you have experienced it, you totally get the devastation, totally understand the emotional wreckage. Your world just blows up in a minute.

As tough as that was for me to experience at age 9-10, to experience that when you’re a 40-something year-old man who’s worked for your father your entire life — it’s madly tragic.

To those who say, “Well, the kids must’ve known. Ruth must have known,” I say, “You’ve lived a very sheltered life. You’ve lived a life in which none of your family ever had secrets.”

Diana B. Henriques is a senior NYTimes financial writer and author of several books on the financial sector. She’s currently working on a book about Black Monday, 1987.

See the rest of this series:

Part One, Q&A: Diana Henriques — How to Interview Bernie Madoff

Part Two, Q&A: Diana Henriques — Psychology of a Ponzi Schemer

Further reading:

NYTimes Madoff coverage (Includes a timeline and archive of Henriques’ articles)

How Bernie Madoff Did It (NYTimes review of Wizard of Lies)

Examining Bernie Madoff, ‘The Wizard of Lies’ (Henriques’s interview on NPR’s Fresh Air)