Want to be a better expert witness, report-writer, or public speaker?

Stop trying to sound smart.

Have you ever been to a PI conference seminar where the speaker droned on and on in too much detail and complexity for the audience to follow? Did you learn anything from him? Did anyone?

It may sound counterintuitive, but knowing too much about a topic can actually make it hard to write or speak well about it. In his book, The Sense of Style, linguist Steven Pinker calls this phenomenon “the curse of too much knowledge.” When you know so much about a subject that you’ve forgotten what it’s like not to know it, it’s difficult to discuss that subject in a way beginners can understand.

Remember What It’s Like to Be a Beginner

When I became a flight instructor, I had hundreds of flight hours in my logbook. But when my first student climbed into the cockpit, I had to relearn what it felt like to fly for the first time. “That is an altimeter,” I would tell them, or “On the ground, you steer with your feet.” I had to be careful not to barrage them with too much information in the first lesson; otherwise, they’d go home feeling overwhelmed and discouraged.

These students trusted me to teach them to pilot an aircraft. Showing off my abilities would not help them achieve that task. In the cockpit, my ego did not matter. I had to remember what my students didn’t know, and what it was like to be an uncertain beginner. That required imagination and empathy.

These students trusted me to teach them to pilot an aircraft. Showing off my abilities would not help them achieve that task. In the cockpit, my ego did not matter. I had to remember what my students didn’t know, and what it was like to be an uncertain beginner. That required imagination and empathy.

Sometimes, as an investigator, you’ll need to do the same thing: Remember what it’s like to know nothing about your subject. Leave your ego behind.

Consider Your Audience

Let’s say you’re testifying as an expert witness. The jury doesn’t understand ballistics, cell phone tower pinging, or DNA analysis — whatever you happen to be discussing. If you speak to them as you would to a colleague, using jargon and assuming a baseline of knowledge, they won’t get your point, and you’ll have done no favors for the attorneys who called you to the stand.

I get it: It’s tempting to show off your knowledge. We all want to “sound smart,” and we too often succumb to the temptation to pepper our articles or speech with big words, specialized terminology, and stuffy bureaucratic language.

PIs aren’t the only culprits. You can also find this kind of dense prose in academic and scientific writing, corporate mission statements, and political punditry. It’s boring and nearly impossible to read, as if the writer or speaker didn’t want us to understand his meaning.

We’ve all had teachers like this in school: people who were too busy showing off to actually impart their knowledge to students. They left us feeling frustrated and, often, not liking whatever subject they taught, and that was a disservice to everyone.

We’ve all had teachers like this in school: people who were too busy showing off to actually impart their knowledge to students. They left us feeling frustrated and, often, not liking whatever subject they taught, and that was a disservice to everyone.

When you’re testifying, teaching a course, writing a how-to article for investigators, or producing a report for a client, remember that your audience may know far less then you do about your field.

Put yourself in their shoes. Be your audience. Imagine the experience they are having as they read or listen. Is it a good one?

Don’t treat them as if they’re stupid just because they don’t know your subject. Just be clear and patient. Keep your language simple, and carefully explain concepts they may not understand as well as you do. Repeat the explanations as needed. Avoid jargon whenever possible, and if you must use it, define the terminology.

Remember: When you’re writing, testifying, or teaching, all that knowledge you have locked inside your head isn’t doing anyone any good if you can’t impart it. Showing off won’t help you accomplish your mission — of telling a great story that teaches, persuades, or inspires.

3 Ways Not to Write an Investigative Report (and One That Works)

Let’s take an example from a made-up investigative report. The first is written in a style commonly found in reports written by investigators or police detectives. (It’s a satire, of course, but not by much.)

The problem with this sort of “officialese” is that it requires about three careful readings (and six cups of coffee) to figure out what is actually going on. The report-writer has used far more words than he really needs, and it’s still not clear who has done what, and when.

Let’s find a way to say this better. First, we’ll replace the passive verb construction “was called into question” with an active verb and reverse the order of the sentence:

This version is an improvement on the first one, but only slightly. By reversing the structure, we’ve managed to shorten the statement and replace the passive “was called into question” structure with an active (albeit stuffy) verb, “controverted.”

We can do better. Let’s eliminate the ponderous phrases, “presentation of video evidence” and “veracity of the subject’s statement.” By replacing words like “veracity” and “presentation” with more specific and ordinary words, I think we can get a little closer to the facts of who did what, when:

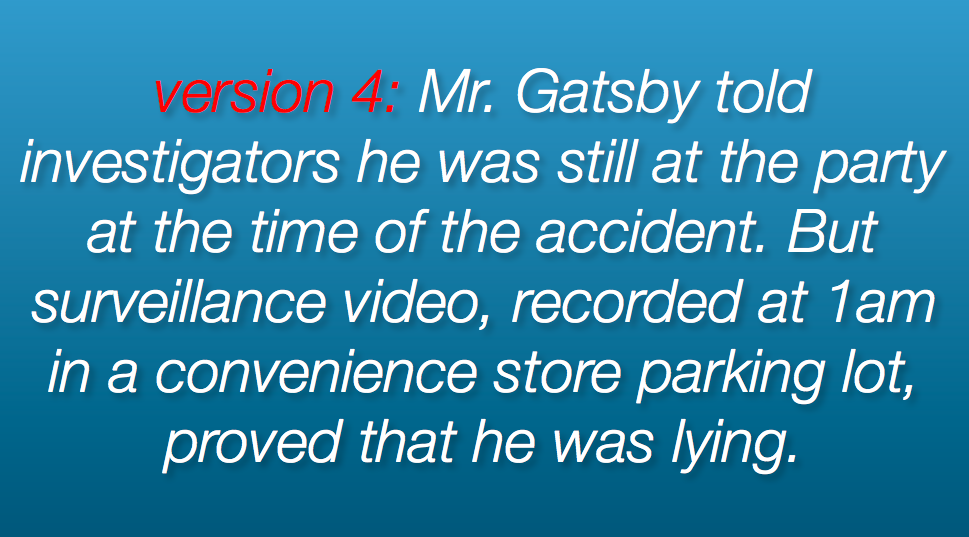

We’re almost there. Now let’s get even more specific. Why not just say who and what we’re talking about instead of referring to “the subject” and “the event in question”?

It’s not a beautiful piece of writing, but at least it’s clear. We know who did what, when, and why it matters to the case.

We’ve eliminated passive verb constructions and vague, windy phrases like “the subsequent presentation of,” and we’ve chosen more specific nouns and verbs that nail down the details. This version is still shorter than the first one, but it contains much more information.

When you’re writing to convey information, as in an investigative report, your goal is to get to the point using as few words as possible. A simple style is best for this purpose. Avoid the temptation to use bigger, fancier words like “individual” or “utilize” when “person” or “use” will do just as well. Don’t “implement a cancellation.” Just cancel!

Skip the flowery adverbs and adjectives if they don’t add important information. Try to use active verbs and simple constructions — subject, verb, object — as in “X did Y to Z.”

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]YES: “Ms. Medea’s ex-husband set her dress on fire, and she turned and ran toward me.”[/quote]

This gets to the point much more effectively than a reversed, passive construction:

[quote align=”center” color=”#999999″]NO: “Investigator was approached by an individual whose garment had been set aflame.”[/quote]

Conclusions

Effective prose isn’t about showing off, pretending to be more sophisticated than you are, or making other people feel stupid. In fact, it’s just the opposite: Great writing makes people feel smart, because it’s clear and easy to understand.

At its very best, writing and speaking can change people’s ideas. And when you speak at a PI conference, testify at trial, or write for PursuitMag, that’s exactly what you’re trying to do.

Source:

The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century, by Steven Pinker

See also:

Five Fast Improvements to Your Investigative Reports

Plain English for Investigators