The Pinkerton National Detective Agency presaged the rise of federal law enforcement — and private security firms operating in ethical borderlands.

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency was one of the first, and certainly most successful, private detective agencies in America. It was founded by Allan Pinkerton, a staunch abolitionist from Glasgow who fled Scotland in 1842 and moved to Chicago, where he established a barrel-making shop that was also a stop in the Underground Railroad. After stumbling upon a band of coin counterfeiters and helping apprehend them, he was appointed a county deputy sheriff and later became Chicago’s first police detective and an agent for the U.S. postal service.

In 1850, Pinkerton left the force and created the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which specialized in security for railroads and express companies. An early logo for the company, which featured a drawing of a sleepless eye, inspired the term “private eye.”

Kate Warne, the First Female Detective

One day in 1856, a young woman walked into the Pinkerton agency to apply for a job as an investigator. Allan Pinkerton was initially skeptical. But Kate Warne, around 23 years old, assured him that she could “worm out secrets in many places to which is was impossible for male detectives to gain access,” as he recalled in his memoir.

Indeed, she did: Warne helped solve an embezzlement case by befriending the prime suspect’s wife, and Pinkerton asked her to head a division of female detectives in 1860. Allan Pinkerton headed a Union intel-gathering service during the Civil War, and in 1861, helped thwart a plot to assassinate President Lincoln. He’d gotten a tip about the plot and sent several agents, including Warne, to infiltrate pro-Confederate circles in Baltimore. Undercover as a coquettish Southern belle, Warne learned about the details of the conspiracy to kill Lincoln while he transferred from one train to another by carriage in Baltimore. She posed as his caregiver on the journey and helped him change trains safely.

Notoriety and Legacy

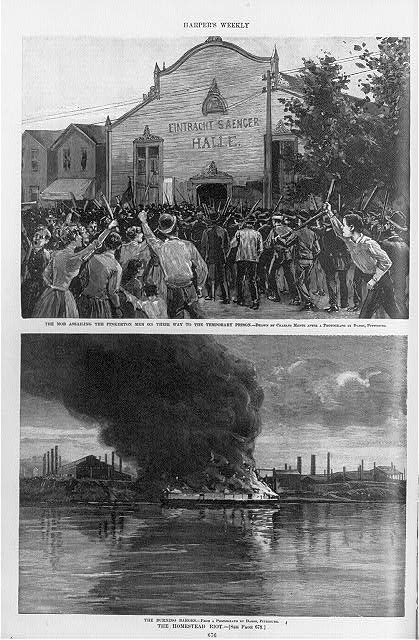

In the 1870s, the Pinkertons worked as bounty hunters in the lawless Wild West, chasing outlaws like the Reno Gang, the Wild Bunch, and Frank and Jesse James. Allan Pinkerton died in 1884, leaving the company to his sons. By the 1890s, the Pinkerton agency employed around 2,000 detectives and 30,000 reserve agents — a larger force than the standing army of the U.S. — and had become notorious for infiltrating unions and strikebreaking on behalf of big-time industrialists. At the infamous Homestead Strike, more than 300 Pinkertons were hired by Carnegie Steel to break a union strike at the Homestead, Pennsylvania mills and furnaces. Both strikers and agents died in the ensuing battle, and the Pinkertons gained a reputation as ruthless corporate henchmen and violent union busters. The state of Ohio outlawed them, concerned that they might operate as a private army — to nefarious ends.

The Pinkertons still don’t sleep — the firm exists today, owned by a Swedish security company and operating under the name “Pinkerton.” The company specializes in risk management and security.

But beyond their continued existence, they leave several legacies, for good and ill: The agency’s “Rogues Gallery’, a database of known perpetrators and suspects that included mugshots, newspaper clippings, and criminal histories, presaged national crime databases like the one maintained by the FBI today.

In filling a niche between spotty local law enforcement and a nascent national law enforcement body, the Pinktertons were a kind of forerunner to the FBI and the Secret Service. They also foreshadowed the rise of private security firms like Black Cube and Blackwater, built by ex-spies and operating in the borderlands of morality and ethics.

Perhaps most of all, the Pinkerton agency paved the way for a beloved literary genre — by hiring and training one of its creators.

The Making of Dashiell Hammett

Sam Hammett, a high-school dropout, joined the agency in 1915, when he was 20 years old. He worked on and off shadowing smugglers and philanderers until 1922, when complications from TB and his objections to the agency’s anti-union militancy prompted him to “retire” from sleuthing. Hammett later declared that he “liked gumshoeing better than anything I had done before.”

“I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble.” —Sam Spade

Then he turned to writing. Sam, using the name “Dashiell Hammett,” went on to create iconic characters like Sam Spade and Nick and Nora Charles; the New York Times called him the “dean of the so-called ‘hard-boiled’ school of detective fiction.” His stories were a departure from the staid sleuthing of Victorian-era, drawing-room detective fiction.

As Hammett once wrote to his editor, “Someday somebody’s going to make literature out of detective stories …” By writing what he knew, the iconic PI-turned-literary star did just that.

Sources:

Women Detectives in Fact and Fiction, by Erika Janik (CrimeReads, 2016)

10 Things You May Not Know About the Pinkertons, by Evan Andrews (History.com)

“Andrew Carnegie once hired a militia and converted factories into makeshift forts to battle striking workers,” by Meagan Day (Timeline.com)

The Case of the Vanishing Private Eyes, by Benjamin Welton (The Atlantic, 2015)

A Reasonable Amount of Trouble, by Bill Demain (PursuitMag)